Berlin stations. New shades and textures of the organic functionalism

by José Calvet

Berlin, during the Republic of Weimar, was living an important socio-economical moment with innovations in the mobility infrastructure and city urban planning. In the Romantic period, Peter Joseph Lenné and Friedrich Schinkel already had developed strategies to define the city public spaces. They designed parks, squares and green streams integrated with water canals that can be seen today in ‘Tiergarten’, ‘Landsberg Kannal’, ‘Volkspark Friedrichshain’ and ‘Pfaueninsel’, with each of their designs being part of Berlin’s urban culture and territorial definition. These urban developments provided a certain personality to the region, the city public spaces and future developments.

A new modern spirit, came after the Austrian architect Otto Wagner, Wien Grossstadt (1911) plan and district definition that improved the notion of collective property and its programmatic mix use, in each district. This infinite and regular urban web facilitated the distribution of the public buildings, of 23 meters width streets integrating different systems of mobility, and limiting urban densities between 100.000 and 150.000 inhabitants per district. He imposed a web to the city periphery while reordering the old downtown grid, that determined a new normative for the mobility systems and pedestrian circuits. This was the first attempt to discuss the transition of the old medieval city to a growing compact city, contrary to Camillo Sitte concerns about the medieval public spaces, with its historical accidents, confined to a local architectural operation and characteristic urban definition.

It is important to understand that the German Weimar Republic urban planning improvements are not only relevant by the integration of the future ‘Autobahn’ culture, that was spread out with Martin Wagner’s (Berlin city planner from 1925 to 1932) departure to the U.S., but also by the effort in articulating the city urban settlements with the already existing mobility systems of the ‘Ring Bahn’ and ‘Stadt Bahn’ projects, developed during the 18th and 19th centuries. The new culture of the Highway and the Subway expansion is the challenge of German city planners of the 20’s to incorporate new models of housing.

The ‘Siedlung’ (the settlement) takes the function of the urban form and the advantage of its organic characteristics, ‘mesh’, adapting to different territorial elevations, each with a different mobility concept. The emergence of the Highway is something that the Wien Grossstadt plan couldn’t take into account because of its regular and strict growing circular web that, on the other hand, solved the excessive density problems from the ‘Ring’ urban planners. However, it forced the irregularities of the territory to adapt to an infinite regular matrix.

Martin Wagner saw the problems that the Ring strangulation generated in the city of Berlin, with high levels of urban density and the excessive speculation of the private property. He envisioned, with the growing possibilities of the city, a different approach that would maintain some of the old towns original characteristics. After the Greater Berlin Act (1920) that aggregated several new districts to the ‘Berliner Ring’, some of them were already relevant historical towns, like Charlottenburg, Köpenick, Lichtenberg, Neukölln, Schöneberg, Spandau and Wilmersdorf and were now part of the greater Berlin perimeter.

It is this ability to take advantage of different mobility transport modes that helps to characterize different housing types in each urban development, during the Weimar Republic. With the pedestrian use it makes some of these interventions so attractive in some restricted operations executed in various frames of the city. This is so relevant as to think that mobility projects can give certain ‘semantic’ structures that makes it possible to play with its social significances, avoiding to implement similar rules for the old towns that, afterwards, became new districts of the city of Berlin. Those semantics are the social significances taken from the mobility concepts – syntax – implemented in the topography.

M. Wagner came with tactile solutions using a modern urban lexicon, together with the already executed old Garden Cities projects, using their green belts that were implemented next to the Ring Bahn and Stadt Bahn, now to be in dialog with the ‘Siedlungen’ projects connected to the subway extension, while, as Berlin ‘Stadtbaurat’ (city director of urban planning) defined strategies for the Highway to go in and out of the old Prussian city gates.

The slope, the ditch, the loop, and the belt are the urban “strategies” that the train, the subway and the highway took to contain or extend parts of each urban development. These elements are so important to include or exclude new urban frames that permit a careful and progressive appropriation taken by different urban polarities and allowing the continuous growth of the old towns footprint in the Great city. It is the varied use of time and space perception, favouring the pedestrian use, where different types of housing/industries/commerce/public spaces/public buildings can coexist that accelerates the transformation of the urban tissue and permits its continuous mutation.

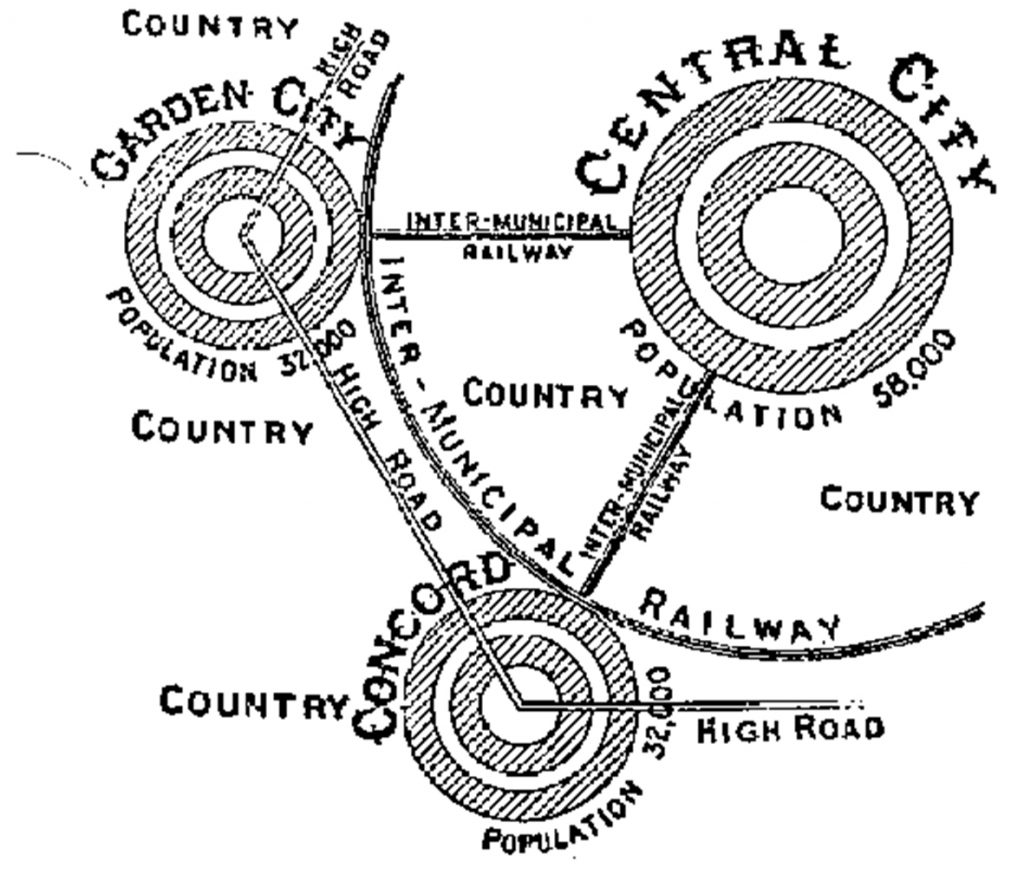

‘Blowing Bubbles’

What I here designate as ‘Bubbles’ are the urban areas connected to the city mobility infrastructure. Usually, they are smaller than a district and have a bigger scale compared to an urban settlement and each at least have one subway or train station associated. Sometimes they are open to the city administrative centre of Berlin, to a

The Bubbles in the opposite direction, usually open to the peripheral edges, are the prior old town planning of the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. These have different garden concepts related to the 19th century hygienic concerns with lakes and gardens specially designed to relax. The city train (with less stops) is the main mobility infrastructure with a train station connected to a park close to the urban developments.

The ‘growing house’ concept proposed at a beginning by the landscape architect Leberecht Migge with his community gardens and private orchards, is one of the most relevant influences of the 20’s Weimar republic that contributed for the ‘growing house’ and respectively the ‘growing city’ of Martin Wagner. The garden is no more a stable place of beauty to enjoy at a distance but a place of producing people’s own food and to generate community relations within the ‘Siedlungen’ progressive growth. (Haney, 2010).

The garden is a buffer zone, the ‘mesh’, impregnated of cultural activities and true anthropological meanings where topological footprints arose, to then extend the house and the city. This buffer zone can sometimes be in-between two or three different old towns and might impel different agricultural productions. The sense of community would dictate the transformation of the city edges conformation from a previous topographical prefiguration. The cultural habits of production and organization in each place would, then, dictate the public and private uses of each group of settlements.

The station would be an engine for the activities held in the public spaces and plazas. At a bigger scale, the city mobility infrastructure, the territorial ‘grid’, is the barrier with their thresholds that can condition the territory significances and set various openings for the city transformation. The mobility systems are in constant configuration and reconfiguration. The urban narrative happens when the housing settlements generate different ‘patterns’ in the territory by the community habitability.

The theme of the form and its discussion within the German architects group “Der Ring” shows the impact of the Wasmuth Portfolio entitled “Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright”, 1910, in the German architectural culture. The dialectic about form and the means to produce it are present in relevant articles such as “Wege Zur Form” (Häring, 1925 apud Jones, 1999). The discussion about ‘content’, ‘use’ and function were the topics in the table in the architectural office that Hugo Häring shared with Mies vand der Rohe in Berlin (Jones, 1999).

Blundell Jones’ analysis of Häring’s work and theory also refers to a Wright’s expression “The thing that comes out of the nature of the thing” (Jones, 1999), manifesting a possible triad in the semiosis “The Thing”, “The nature” and “the nature of the thing”. This expression is part of the exhaustive analysis of the form taken by “Der Ring” who followed

We might infer that an ‘ecological thought’ of the use of our territory does not correspond to an assertive definition of an existing nature, as Tim Morton supports. Each region has its own resources within the morphological context that have been altered sequentially during different époques. This notion cannot be understood until we see our cultural activities integrated into a ‘mesh’, separated from the hypothetical idea of its territorial origin, but instead placed within its different historical traces. “Isn’t the whole less than the sum of its parts?” (Morton, 2016).

Arguably the mesh theorem by Morton (Morton, 2010) suggests something as clear as this. The mesh might have its possible grid as Wright´s notion of nature possibly its thing as explained in Morton’s interdependence theorem in two axioms. The first axiom explains the polarity of two different identities while the second axiom explains the diachrony stating that, in time, one thing comes from another. Another curiosity from F. L. Wright was that he, just like the philosopher Timothy Morton, was an admirer of Percy Shelley’s poetry. “The original impulses may reach as far inward as those of Shelley’s poet, be quite as wayward a matter of pure sentiment, and yet after the thing is done, allowing its rational qualities, is limited

It is also relevant to state the relevance of ‘topology’ and its potentialities to understand the effects of the grid in a mesh. The ‘seven Bridges of Konigsberg theorem’ from L. Euler, in 1736, is a pre-topological mobility problem that identifies four separated neighbourhoods by a river. The impossibility of crossing seven bridges just once in a singular movement sets the problem: take one bridge out and it is possible to do it in a singular circuit without crossing the nodes/bridge repeatedly. Comparatively, the Station and its Infrastructure are like the bridge and the river, as a starting point for the field of topology and the mobility systems in the territory, defining regions in topology, its possible connections and space fields mutations. The topology advances in geometry came from the Gestalt development in psychology theories (Marcolli, 1978) and are of great interest to revise the terms of the ‘mesh, the ‘grid’ and the ‘patterns’ resulted from them (see Figure 2).

The Grid and the mesh. Alfred Grenander’s subway stations in Weimar Republic

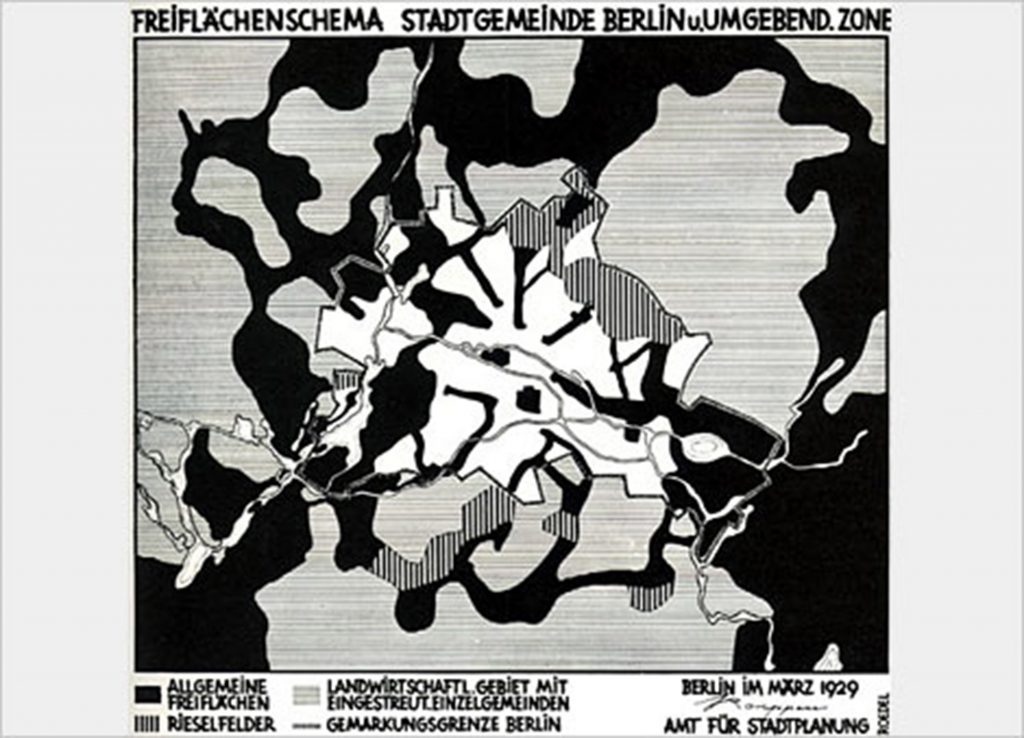

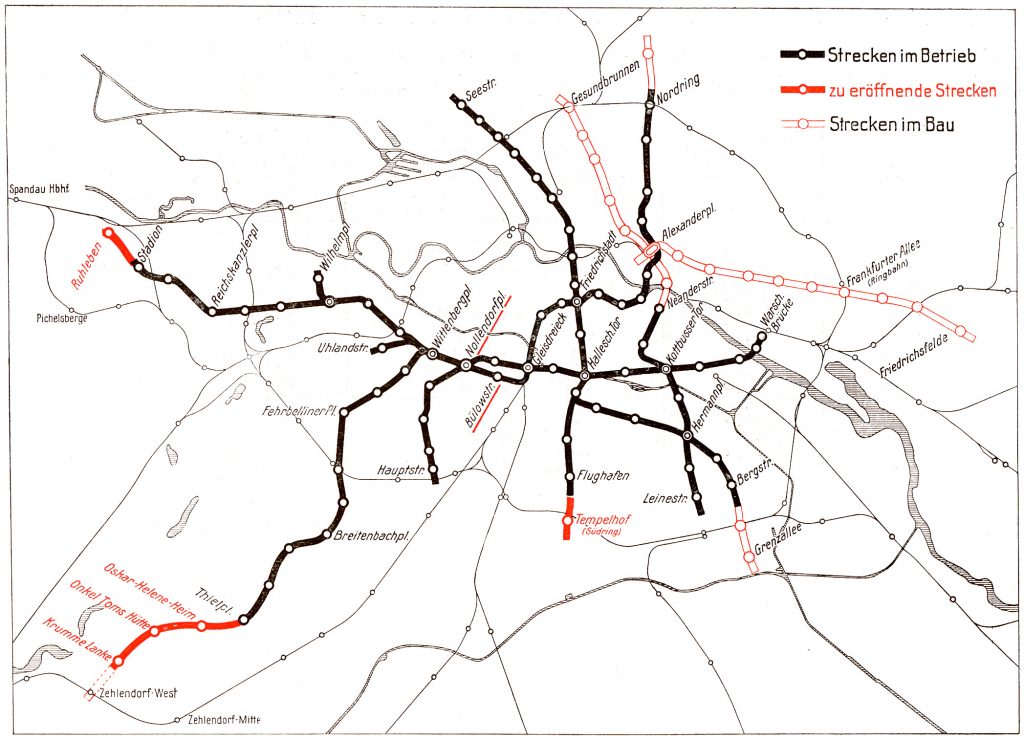

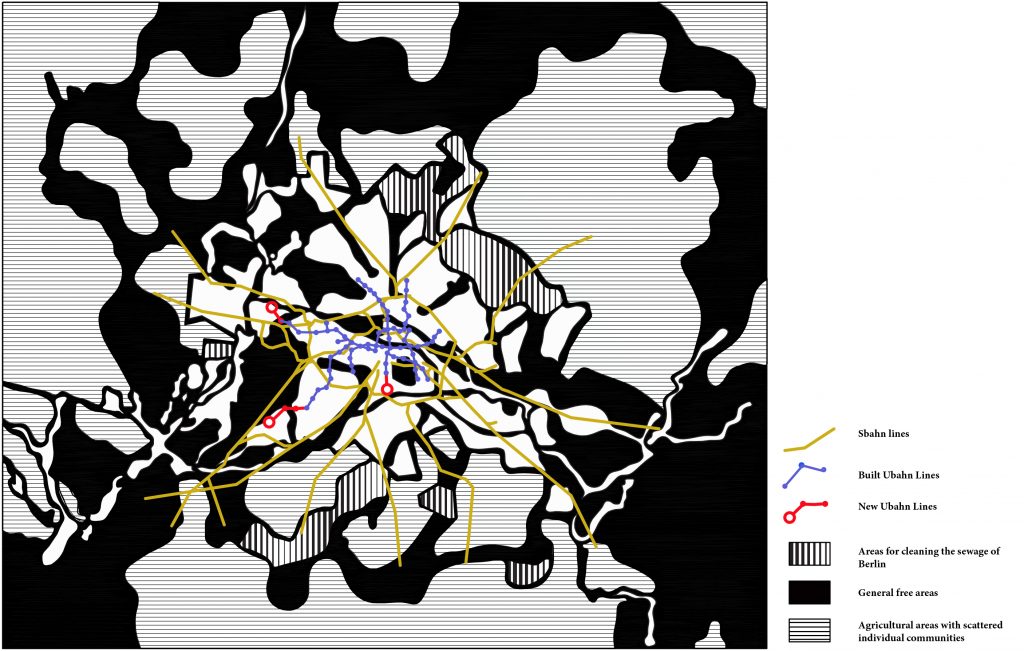

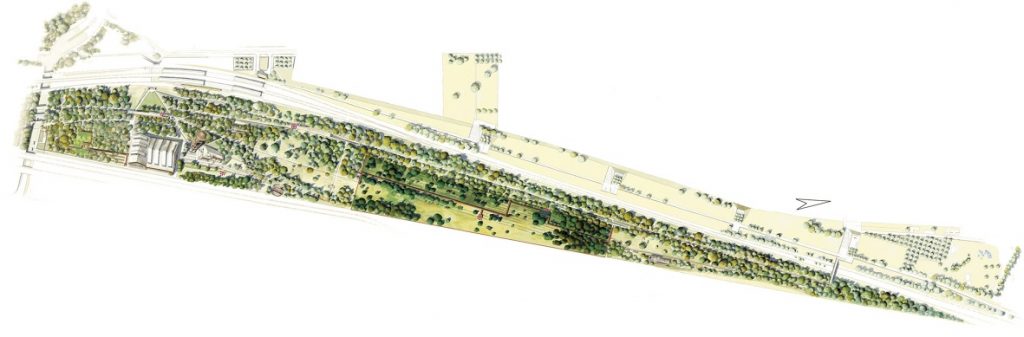

Between the two World Wars, Berlin lived a pivotal socio-economical moment. This was reflected in technological advances used in many buildings and in a swift evolution of the urban built environment. In this respect, the Berlin Freiflächenschema (see Figure 3) developed by Martin Wagner (1929), a plan based on Jansen’s Plan for the Greater Berlin Competition (1909), focused on the importance of the region qualities, where he highlighted its free and green areas. This plan will be of great importance to understand many terminal stations of the lines AI, AII and CII (1929), designed by Alfred Grenander (see Figure 4), with a different strategy compared to a more cosmopolitan version of the line D Nord-Sud Bahnhof (see Figure 5).

Alfred Grenander (1863-1931) designed several of the subway stations in Berlin of Weimar Republic, together with Martin Wagner (already working as “Stadtbaurat”). These stations came after Grenander has worked for the elevated railway company Hochbahngesellschaft and the Romantic generation that developed the Ring Bahn and the Stadt Bahn, during the Wilhelm period in Berlin.

The urban operations led by Martin Wagner with Alfred Grenander Stations are relevant to understand the relations of German town planning from the beginning of 20th century in Berlin Sud-Schöneberg and the reconfiguration of Priesterweg Train station, in 1928. And also correlate the Berlin-Tempelhof train station transformations, from 1929 to

It is important to refer that Martin Wagner was ‘Statbaurat’ of Schöneberg (1918) before becoming ‘Stadtbaurat’ of the city of Berlin (1925) after the Great Berliner Act (1920). The urban transformations, perfecting the mobility systems, in the two areas allowed the town planning of ‘Lindenhof Siedlung’, to develop in

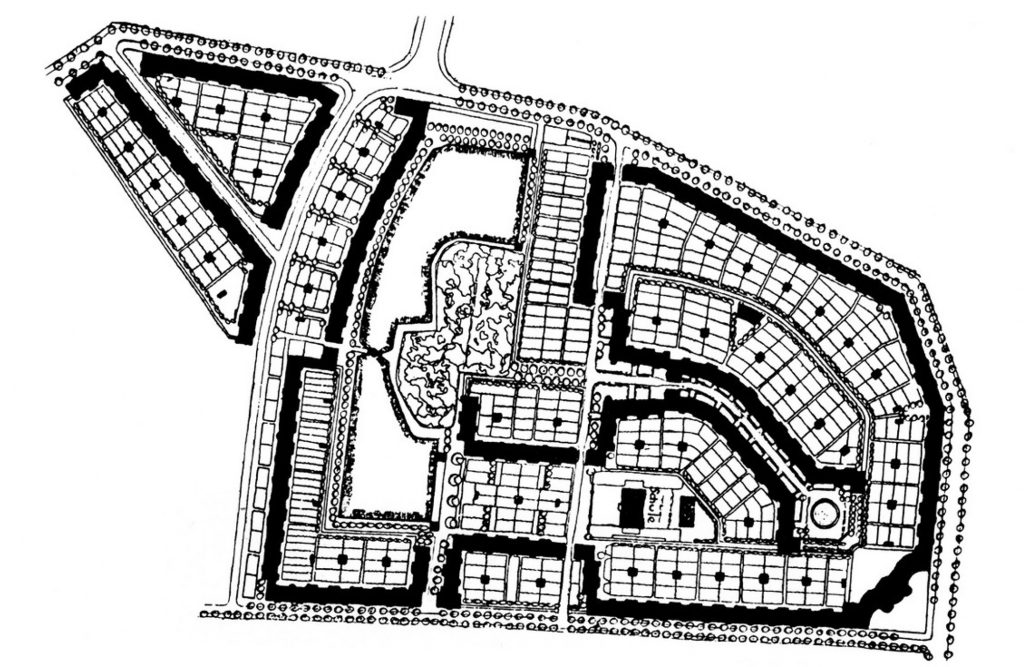

In zone A (see the present situation in Figure 6), the Lindenhof Siedlung (1918-1921) next to Priesterweg train station (see Figure 7 and 8), possibly with Grenander’s intervention, Bruno Taut´s key buildings, Leberecht Migge´s exterior landscape and Martin Wagner´s housing and urban planning. It is important to know that this settlement is one of the first examples of co-housing in Germany, with shared kitchens, and the tenants joining together in an association with community values, after the World War I.

The present situation of this site is the new direct access from the S Bahn station to the abandoned train lines integrated in Schöneberger Südgelände Park, where also is the Priesterweg old station. This site is famous for its endemic species that developed there after its abandonment to then become a protected park.

In zone B (see the present situation in Figure 9), the Neu Tempelhof Siedlung next to Tempelhof ‘ring’ train station (see Figure 10) and Grenander’s Tempelhof subway station (1929). The housing projects began with two semi-circular buildings by Bruno Möhring and Paul

The next Tempelhof airport changes came, ten years ago, turning it into a thematic park that acquired new dynamics between the ‘Siedlung’, the park and the city. The Tempelhofer Park and the Schöneberger Südgelände Park (see Figure 11 and 12)

Conclusion

The Stations are crucial, in our contemporaneity, because of the time-space mix use that is generated within the public space. The station, not only, articulates in itself different mobility transports to stop in the same area but also capacitates the public and private spaces annexed to respond to different public necessities. This is correct because someone that might commute by train in a circuit over 300 km distance has different needs compared to a passenger that is commuting by metro, in a perimeter of 20 km while changing directions continually.

The public spaces that are generated within the Stations are no ‘junkspaces’. As Koolhaas postulated, “Junkspaces represents a reverse typology of cumulative, approximate identity, less about kind than about quantity. But formlessness is still form, the formless also a typology (…) Junkspace is described as space of flows but that is a misnomer; flows depend on disciplined movement; bodies that cohere. Junkspace is a web without a spider” (Koolhaas, 2002, p. 179).

Instead, these spaces are ‘

The modal stations, especially those using different types of mobility transports, are crucial in revitalizing the city public space or to allow a concise urban planning in the city outskirts that, afterwards, can grow progressively. “According to Pacheco, the accessibility and mobility conditions are fundamental in the decision-making on the location and access of interest urban locations, being the large urban centres the most dependent of those conditions. At urban level the land use and land demand, are also dependent on mobility, supported on a more efficient modal split, reducing the distances between points of interest and using, mainly, more sustainable modes of transport, namely public transports, bike and walk.” (Macedo et al., 2017, p. 732)

The ‘hubs’ are the actual possibility to enrich the typology of our contemporary public space. The mobility lines changes over different generations reflect the growing process of the city with station hub need of transformation. This reveals the necessity to reformulate the public space typologies where the station itself is suffering an on-going changing process.

The urban theorist François Ascher favours the permanence of the car, in the future, over the public modal station, even though his recognition to invest in it. That goes along with his idea of a centralized ‘

Nevertheless, the French author enhances the importance in combining the different private and public transports in a single Information Center in a collection of real-time ‘data’ and possible combinations taken by the city citizens (Ascher 2005). Carpio-Pinedo et al. (2014) identify four categories to analyse the issue of ‘land use-transport integration’: “(1) Transport demand and users, (2) Mobility integration, (3) Urban integration, and (4) Land use and urban environment” (Carpio-Pinedo et al., 2014, p. 227). Gebhardt et al. (2016) using the examples of Berlin and Hamburg, argue that also a well-structured intermodality in public transports is possible, i.e. the combination in a single journey of different travel modes, is an essential factor for the development of “sustainable cities”; and consider the emergence of new operating approaches based on demand-oriented services of public transportation.

Lewis Mumford, in the final chapter of his book “The Highway and the city”, argues that good transportation needs to be structured in a way of minimizing costs and favouring the diversity of time spent commuting in order to have multiple choices and reducing unnecessary travels. (Mumford, 1963). He analysed, in the 1960s, the private transport in

This American critic, knowing the possibilities of town planning and regional planning combined together in the landscape, points out where it is most profitable and useful to invest, in transports and which are the effects of each transport mode. He stands for the need of the “Arterial roads” to surround the metropolitan area with park green belts and park free garages, where the land price is cheap. By that

By loosening and stretching the city ‘bubbles’, Mumford analyses the limits for varied social interaction. The urban pattern is connected to the social activities generated by the produced public spaces. The urban developments should corroborate with an accelerated interchange between the private and public investments.

So much for the larger conception of open spaces, as conceived on a new regional pattern, with a permanent green matrix of open areas, preserved for both, and visitors. If we take the necessary political measures to establish this green matrix, a large part of the pressure to escape from the congested city to a seemingly more rural suburb will be relieved, for the rural values that the suburb sought to achieve only for a prosperous fraction of the population – will become an integral feature of every urban community. Two complementary movements are now necessary and possible: one is that of tightening the loose and scattered pattern of the suburb, turning it from a purely residential dormitory into a balanced community, approaching a true garden city in its variety and partial self-sufficiency, with a more varied population and with sufficient local industry and business to support it; and the other is that of loosening the congestion of the metropolis, emptying out part of its population, introducing parks, playgrounds, green promenades, private gardens, into quarters that we have permitted to become indecently congested, void of beauty, and often positively inimical to life. Here, too, we must think of a new form of the city, which will have the biological advantages of the suburb, the social advantages of the city, and new aesthetic delights that will do justice to both models. Now the great function of the city is to give a collective form to what Martin Buber has well called the I-and-Thou relation: to permit – indeed, to encourage – the greatest possible number of meetings, encounters, challenges, between varied persons and groups, providing as it

were a stage upon which the drama of social life may be enacted, with the actors taking their turn, too, as spectators. (Mumford, 1963, p. 230).

The station might be a place of space production and to boost a varied

For a more walkable territory is necessary to enrich our quality of life, thus, to promote more public transport and human energy transportations, like the use of a bicycle. It is, then, imperative to study the rules for a ‘dynamic scale urbanism’ better integrated with our own human conditions and a healthy urban environment.

References

1. Ascher, François (2005, July). Arquitectura de infraestructura: Ciudades con velocidades multiples, un desafio para arquitectos urbanistas y politicos. ARQ 60.

2. Bakhtin (1981). The Dialogic Imagination.Texas: The University of Texas Press

3. Carpio-Pinedo, J., Martínez-Conde, J. A., & Daudéna, F. L. (2014). Mobility and Urban Planning Integration at City-Regional level in the Design of Urban Transport Interchanges (EC FP7 NODES Project – Task 3.2.1.). Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences (160), 224-233. DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.134

4. Fabian, T. (October 2000). The evolution of the Berlin Urban Railway Network. Japan Railway & Transport Review 25, p. 18-25

5. Frantzeskakia, N., & Kabischb, N. (2016). Designing a knowledge co-production operating space for urban environmental governance—Lessons from Rotterdam, Netherlands and Berlin, Germany. Environmental Science & Policy, 62, 90-98. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.01.010

6. Gebhardt, L., Krajzewicz, D., Oostendorp, R., Goletz, M., Greger, K., Klötzke, M., Wagner, P., & Heinrichs, D. (2016). Intermodal urban mobility: users, uses, and use cases. Transportation Research Procedia (14), 1183-1192. DOI:10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.189

7. Haney, D. (2010). When Modern Was Green: Life and Work of Landscape Architect Leberecht Migge. Oxon: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group

8. Jones, P. B. (1999). Hugo Häring: The Organic Versus the Geometric. Fellbach: Edition Axel Menges

9. Koolhaas, R. (2002, Spring). Junkspace. October (100), 175-190

10. Macedo, J., Rodrigues, F., & Tavares, F. (2017). Urban sustainability mobility assessment: indicators proposal. Energy Procedia 134, 731-740. DOI:10.1016/j.egypro.2017.09.569

11. Marcolli, A. (1978). Teoría del Campo. Curso de educación visual. Madrid: XARAIT Ediciones y Alberto Corazón Editor

12. Merrill, S. (2015). Identities in transit: the (re)connections and (re)brandings of Berlin’s municipal railway infrastructure after 1989. Journal of Historical Geography, 50, 76-91. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2015.07.002

13. Morton, T. (2010). The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University

14. Morton, T. (2016). Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future coexistence. Minneapolis, Columbia: Columbia University Press

15. Mumford, L. (1963). The Highway and the City. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

16. Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and Narrative Vol I. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

17. Scarpa, L. (1986). Press Martin Wagner und Berlin. Architektur und Stadtbau in der weimarer Republik. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden Gmbh

18. Wright, F. L. (1901). The art and craft of the machine. Art Humanities Primary Source Reading (50). Retrieved from: http://www.learn.columbia.edu/